The European financial landscape is currently facing a powerful combination of factors that are causing concern in its banking sector and beyond – it has sounded the alarm even though this has not been seen in what the established financial media is reporting.

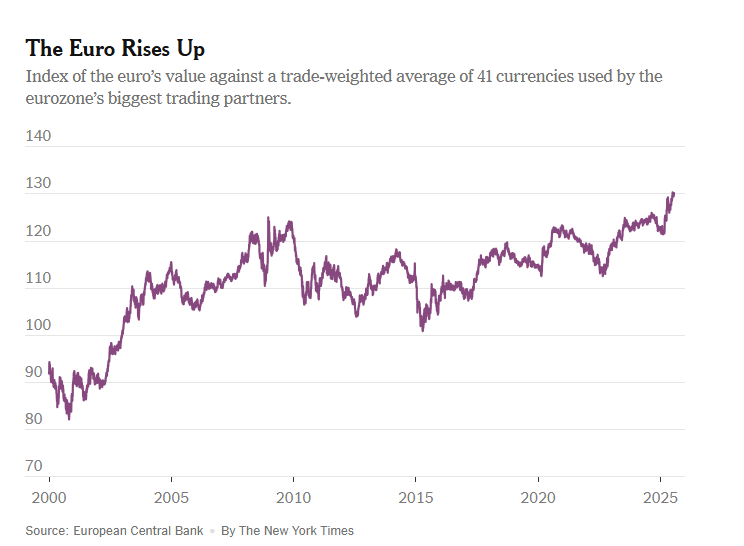

Despite statements by Brussels officials about an “opportunity for the euro” to take advantage of the weakening dollar, the reality is that the European economy, which is facing competitiveness problems in relation to its main trading rivals, the US and China, will be burdened by the appreciation of the euro – with an immediate risk to exports.

The blow to the largest exporting power, Germany, is expected to be severe in the midst of economic stagnation. On the one hand, the persistent strength of the euro poses a complex challenge for exporters and businesses operating on the continent.

On the other hand, the escalating imposition of global tariffs is creating further uncertainty and disrupting established trade flows. This convergence of economic pressures is forcing European banks to reassess their strategies and risk management approaches.

De facto loss of competitiveness

The euro, currently trading at high levels, is a double-edged sword for the European economy. While a strong currency can signal economic confidence and make imports cheaper, it also increases the cost of European products for international buyers.

This directly affects the competitiveness of the continent’s export industries, which are a major growth engine for many European countries.

Impact on Exporters

For European manufacturers and service providers, a stronger euro means that their products and services become more expensive in foreign markets. This can lead to:

- Reduced Demand: Foreign customers may seek more affordable alternatives from countries with weaker currencies.

- Lower Profit Margins: To remain competitive, European companies may need to absorb some of the exchange rate difference, leading to reduced profitability.

- Production Relocation: Some companies may consider relocating production facilities to countries with more favorable exchange rates.

Banking Sector Exposure to Exports

European banks have significant exposure to the corporate sector, including many exporters.

When these businesses face problems due to currency fluctuations, this can translate into:

- Increased Credit Risk: Companies struggling with reduced demand and compressed margins may find it difficult to service their debts, raising concerns about non-performing loans.

- Reduced Lending Opportunities: As businesses face economic uncertainty, their demand for new loans and investment capital may decline.

- Impact on Investment Banking: A more challenging economic climate can reduce the appetite for mergers, acquisitions and initial public offerings, affecting investment banking divisions’ revenue streams.

Share of euro area investment portfolios located in the US.

The Global Trade War and the ECB’s Monetary Measures

Tariffs, essentially taxes on imported goods, are a tool that governments use to protect domestic industries, raise revenue, or exert political leverage. However, in today’s global environment, tariffs lead to increased trade tensions and economic uncertainty.

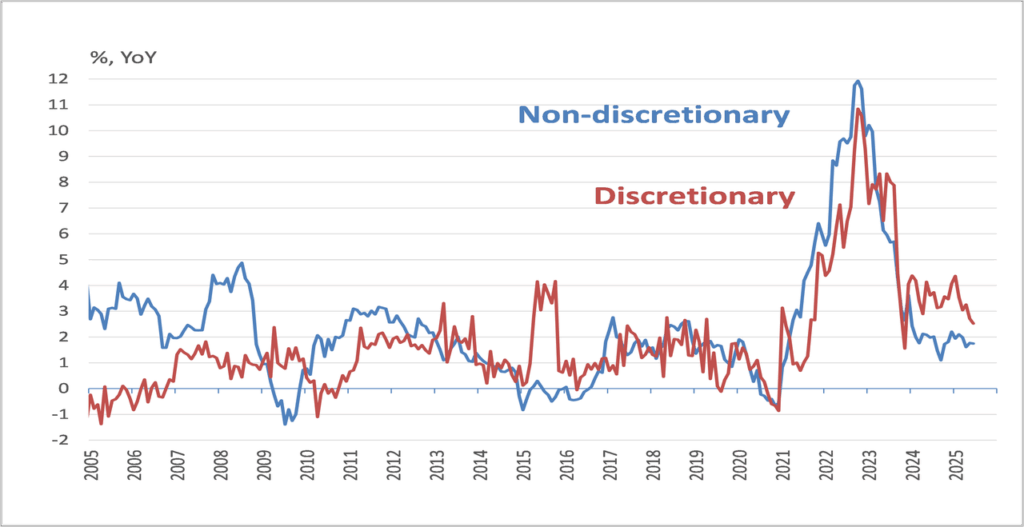

After easing its policy by 200 basis points since last June, the European Central Bank (ECB) left interest rates unchanged this week. At 2%, the deposit rate is right in the middle of its neutral range of 1.5% to 2.5% – which is considered neither too restrictive nor too supportive – giving the Governing Council a chance to take a breather and then reassess the situation on September 11.

Of course, as Christine Lagarde reiterated several times during her last press conference, the economic environment is currently “highly uncertain” and will remain so as long as global trade tensions persist. So while policy is currently “well placed,” further easing may well be required later in the year to help keep the recovery on track. So what could trigger action from the European Central Bank?

As has been the case since March, the ECB is uncertain about how the new normal for global trade will shape itself over a 2-3 year forecast horizon. In the baseline scenario published by the ECB in June, US tariffs on imported goods would be around 10 percentage points higher than last year (20% higher for goods from China) and the EU would not retaliate.

However, a more “severe” alternative scenario involving retaliation is also entirely possible. This, according to the ECB’s estimates, could reduce eurozone GDP by around 1 percentage point compared to the baseline scenario, and would put pressure on the Governing Council to respond.

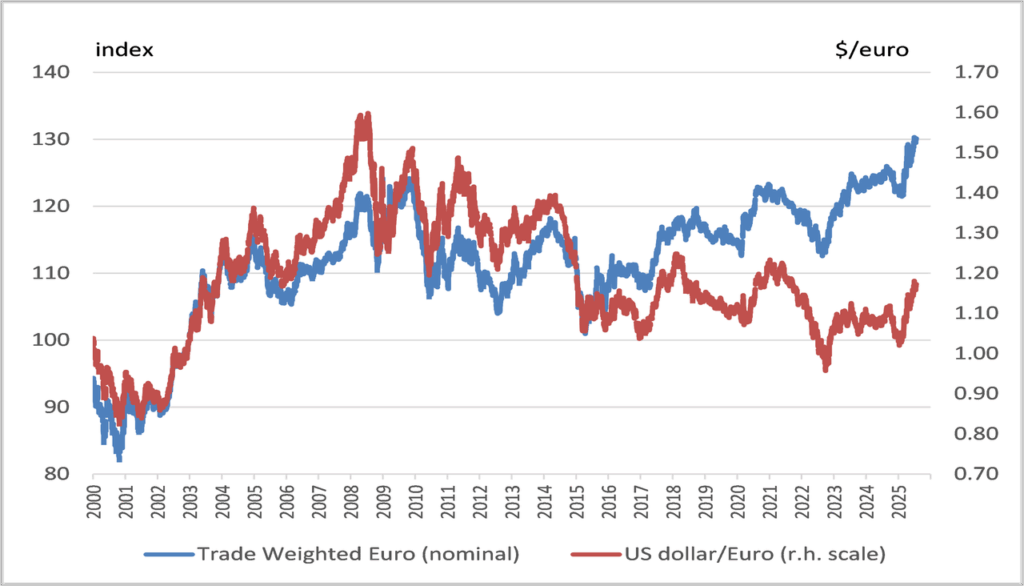

In addition to what might happen to tariffs and trade flows, the ECB is also increasingly focusing on capital flows and the exchange rate.

The benefits for the US of a weak dollar

The US government seems to welcome a weak dollar. And, for now, the ECB is putting up with things and continuing to use its standard coded language of “we are not targeting the exchange rate.”

European Central Bank Vice President De Guindos also said that if the euro rises above $1.20 (currently at $1.175), this could prove difficult for the Governing Council. This much more candid statement suggests that, as some of the domestic inflation measures continue to decline, the Governing Council’s patience with the euro’s strength is starting to wear thin – and any significant further appreciation will require a reaction.

The “Excess” of the Dollar and the Rise of the Euro

The dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency gives the United States an “excessive privilege” – a term begrudgingly coined by a French politician, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, in the 1960s. Because investors, governments and central banks around the world seek the safe, predictable returns of dollar-denominated assets such as Treasury bonds, there is a strong, built-in demand for dollars. This makes it easier for the U.S. government to borrow and boosts the purchasing power of American consumers.

The eurozone, which consists of the 20 countries that use the euro and rivals the United States in size and wealth, has never attracted investors in the same way. The euro ranks a distant second to the dollar in global use.

The euro’s recent rally is a significant reversal from just three years ago, when it fell to parity with the dollar as investors feared damage from galloping inflation and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And it’s a far cry from the eurozone debt crisis of the past decade, when the monetary union at times seemed in danger of collapsing.

As welcome as the euro’s recovery from those episodes has been – the euro is trading near historic highs against the currencies of dozens of major trading partners – it’s also possible to have too much of a good thing.

The Impact of Euro Appreciation on European Exports

As money flows into the euro and into euro-denominated assets such as German government bonds, economists and executives warn that the currency’s strength could hurt exporters.

They are already facing Trump’s tariffs, which make their products more expensive for buyers abroad, as well as increased competition from Chinese rivals in key markets.

Exports were already likely to weaken and slow the eurozone economy because of U.S. tariffs and European government policies that would encourage more imports.

The Trade War Chain Reaction

When one country imposes tariffs, it often triggers retaliatory measures from others, leading to a chain reaction known as a trade war. This disrupts established supply chains and increases the cost of goods for both consumers and businesses.

For European banks, this translates into:

- Increased Volatility in Financial Markets: Trade disputes cause uncertainty, leading to fluctuations in stock markets, currency values, and commodity prices.

- Disruption of Corporate Supply Chains: Many European companies rely on global supply chains.

- Tariffs can make importing essential components more expensive or even impossible, forcing them to find alternative, often more expensive, suppliers.

Companies warn

Some major European companies have warned about the impact of a strong currency on their profits, especially in export-oriented Germany.

SAP, a software company that recently became Europe’s most valuable public company, said that every one cent increase in the euro-dollar exchange rate results in a 30 million euro drop in revenue, without currency hedging.

Adidas, the sportswear brand, said a strong euro had “negative conversion effects” on its overseas sales.

Daimler, the truck maker, said that fluctuations in the euro-dollar exchange rate “could significantly affect” its financial performance.

There is no monetary policy plan to deal with this particular weak dollar situation.

Donald Trump’s strategy of reducing US trade deficits and reviving domestic manufacturing serves his country’s national interests. In this new environment, there is no European response – at the risk of destroying the European economy – and southern European member states like Greece will simply find themselves caught in the middle of the storm…