The lessons learned from the global financial crisis of 2008/2009 seem not to have become commonplace for the operation of the financial system. The turmoil of the past year has shown that further progress is needed in a number of areas to ensure that banks are never too big to fail.

It is noted that almost a year ago, Credit Suisse, a global systemic bank with assets of 540 billion dollars and second largest Swiss bank, founded in 1856, collapsed and was sold to UBS.

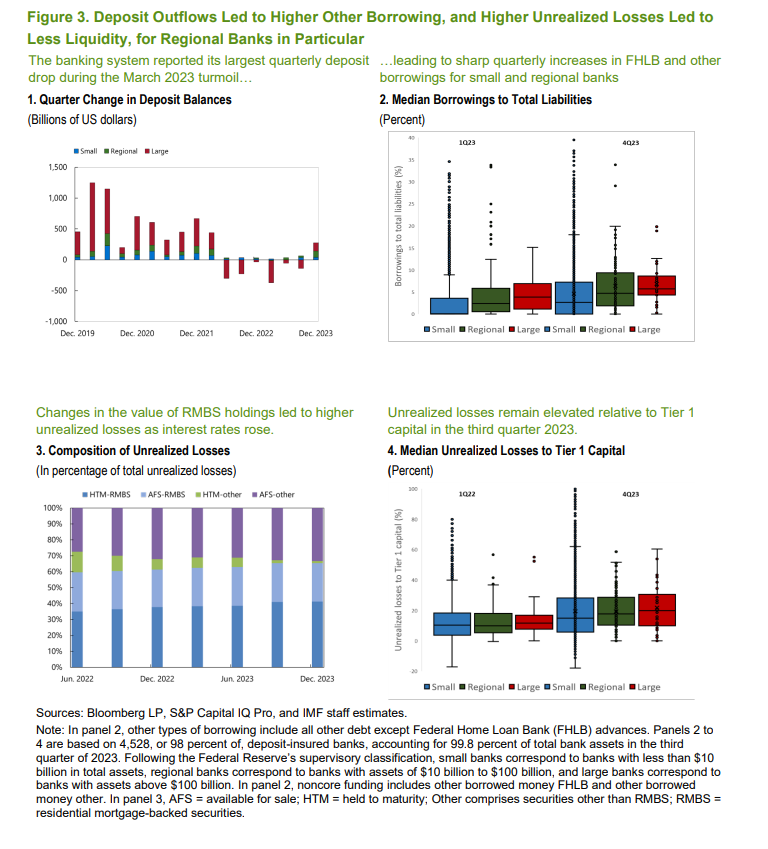

In the United States, Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank collapsed around the same time amid the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes aimed at curbing inflation.

Totaling $440 billion in assets, the regional banks marked the second, third and fourth largest bank failures since the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was created during the Great Depression in the 1930s.

This banking turmoil represented the most significant test since the global financial crisis in which systemic banks were bailed out in order to preserve financial stability and protect taxpayers.

What’s new?

In short, while significant progress has been made, further work is needed, IMF economists diplomatically say, while the context of their research points to the risk of a new domino of banking collapses.

On the one hand, as noted in a recent IMF report, authorities’ actions last year successfully averted deeper financial turmoil, and financial soundness indicators for most institutions signal continued resilience.

Moreover, unlike many of the bankruptcies during the global financial crisis, this time significant losses were shared with the shareholders and some creditors of the failed banks.

However, taxpayers were once again paying part of the damage, as extensive public support was used to protect the overall stability of the banking system – more so to secure the deposits of the failed banks.

Amid a deposit flight, Credit Suisse’s takeover was backed by government guarantees and liquidity almost equal to a quarter of Swiss economic output.

What have we learned from the developments?

Intrusive surveillance and early intervention are critical. Credit Suisse’s depositors lost confidence after chronic governance and risk management failures.

In the US, failed banks followed risky business strategies with inadequate risk management. The supervisory authorities in both cases should have acted more quickly and been more dynamic and decisive in their interventions.

The recent review of supervisory approaches found that capacity and willingness to act remain critical — and may include unclear mandates or insufficient legal powers, resources and independence, as well as pressure from powerful financial sector lobbies. Policymakers need to better empower banking supervisors to act promptly and with the necessary regulatory authority if needed. Even smaller banks can pose systemic risks.

Supervisory and resolution authorities should ensure adequate recovery and resolution planning for the sector. This should include banks that may not be systemic in all circumstances but could be in some.

This was a key recommendation of the IMF’s latest Financial Sector Assessment Program for the US. Regimes for resolution procedures and rescue planning need sufficient flexibility.

Policymakers should ensure that rules and resolution plans are flexible enough to balance financial stability risks and taxpayer interests. Government support may still be required in some cases – for example, to avoid a systemic financial crisis.

The IMF recommended the equivalent of a systemic risk exemption for the euro area, for example. While the authorities should continue to pursue plan A, they need the flexibility to depart and combine, for example, different resolution tools as required by the specific circumstances at the time of the crisis. Liquidity in resolution is critical.

Banks usually fail because creditors lose confidence, even before the balance sheet reflects potential losses. Building capital buffers in resolution may not be sufficient by itself to restore confidence.

Authorities need to make further progress on how quickly banks headed for resolution could receive liquidity support – including collateral posting and test readiness – while protecting central banks’ balance sheets, according to the IMF.

Authorities in many countries need to strengthen deposit insurance regimes—as we suggested in Switzerland. New technology such as 24/7 payments, mobile banking and social media have accelerated deposits. Last year’s failures followed rapid deposit withdrawals, and deposit insurers and other authorities will have to be ready and able to act more quickly than many today.

The US banks that failed followed extreme practices – with balance sheets that grew too quickly, financed by a high degree of uninsured deposits – so they were largely in the air.

Where the need for wider deposit guarantee coverage is considered, it should be adequately funded.

Particularly in countries with deposit insurance not backed by a deep-pocketed sovereign, policymakers should be careful not to overextend deposit insurance coverage. If not supported by a commensurate increase in deposit insurance, depositors could quickly lose confidence.

Τoo big to fail

The bottom line is that progress has been made, but more remains to be done to put an end to the logic that a systemic bank is “too big to fail.” The bank failures of the past year have provided a valuable check on the progress policymakers are making on the reform agenda and in setting the course for covering the remaining ground. Banking crises are upon us…